A retired number tribute like no other

The retirement of a uniform number is arguably the highest honor that a team can bestow upon a player. The tradition began in 1925, when the University of Illinois’ football team set aside number 77 for Red Grange. The reasons for a number retirement start with a recognition of excellence, of course, but tragedy and sentimentality are not too far behind. The Toronto Maple Leafs’ Irvine “Ace” Bailey became the first pro athlete to have his number retired, back in 1934, when his career ended after a fight against the Boston Bruins.

Nearly a century after Grange’s jersey was put aside, retired numbers aren’t quite the honor that they used to be. The New York Yankees have removed 21 numbers from circulation, the Boston Celtics have mothballed 23 numbers, and individuals such as Wilt Chamberlain and Nolan Ryan have had their numbers retired by multiple teams that they suited up for. Taking the honor to a whole ‘nother level, Jackie Robinson’s 42 and Wayne Gretzky’s 99 have been earmarked for immortality by their entire respective leagues.

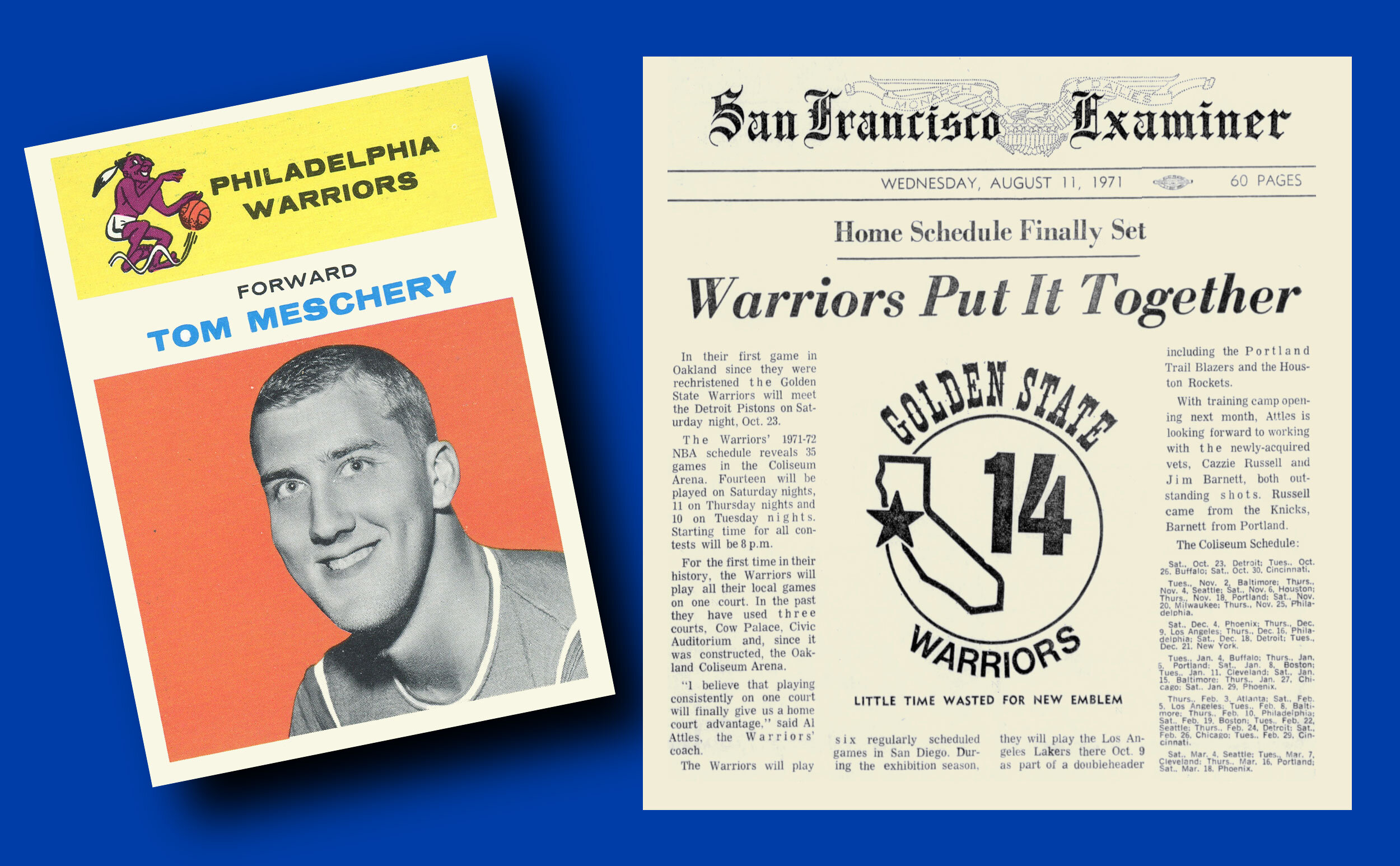

While having one’s number retired is indeed an extraordinary distinction, having one’s number retired AND having it included in your team’s logo is a pretty unique thing, and one but individual can boast of this dual distinction. He was born Tomislav Nicholiavich Mescheriakov in Harbin, Manchuria, in 1938, but achieved sports immortality as Tom Meschery. The NBA’s San Francisco Warriors hoisted his uniform number 14 to the rafters for all eternity on October 13, 1967. That number was incorporated into the club’s logo the following season.

It’s entirely appropriate that such a unique honor is connected to an uncommon individual.

Meschery’s family fled Russia’s 1917 October Revolution, settling in what is now China. While his father was able to secure a visa to emigrate to the United States, Tom, his sister and mother later found themselves confined to an internment camp in Japan during the entirety of World War II. The family reunited in the States in 1946 and settled in San Francisco. Tom attended college at Saint Mary’s College of California, located about 20 miles east of San Francisco. A basketball First Team All-American, he was a key component of the Gaels’ run to the NCAA Tournament’s Elite Eight in 1959.

He was selected by the Warriors, then located in Philadelphia, as the seventh overall pick in the 1961 NBA draft. Meschery and the Warriors relocated after his rookie season, to his adopted hometown, San Francisco. He played a total of six seasons for the team, averaging 12.9 points and 8.5 rebounds per game while garnering a spot in the 1963 NBA All-Star Game.

While Meschery was powering through a stellar NBA career, he was also cultivating a deep-seated love for poetry. “I see poetry in all things,” he told syndicated columnist Murray Olderman in 1967. “Carl Sandberg said once, ‘When will the poet and the machinist get together?’ Certainly, there’s poetry in sports, Most important, there’s poetry in basketball because it’s a love of mine.” Years later he expanded upon things during an interview with NBA.com, saying “We’re Russians, and for Russians, poetry is an important part of our heritage. On my mother’s side, we have a very strong literary heritage. My maternal grandmother’s family are Tolstoys, related to Leo Tolstoy and Aleksey Tolstoy. So I have those literary genes in me and they came out at a young age.”

Meschery’s tenure with the Warriors came to a conclusion when he was selected by the Seattle SuperSonics in the 1967 NBA expansion draft. (Yet one more interesting note to add—Meschery, then 29 years old, planned to retire from basketball and join the Peace Corps. He opted to join Seattle instead.) He wound up playing for the Sonics for four seasons before finally retiring from the game in 1971. He had a position lined up to teach creative writing at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, but decided to take the job as head coach of the American Basketball Association’s Carolina Cougars. He began to write in earnest during his time in Seattle and he hasn’t stopped. Now 82 years old, Meschery is a published poet and writing teacher.

The Warriors retired his uniform number 14 prior to their season opener on October 13, 1967, against Meschery's SuperSonics, the first game for the Seattle franchise.

But what about the logo? And why was this singular honor bestowed upon this particular player? The easy explanation is that there are times in life and in history when comets collide and two individuals combine in a way that is both rare and wonderful.

This brings us to Warriors owner Franklin Mieuli (1920-2010,) a charismatic and fascinating individual in his own right. Mieuli’s interests in promotion and branding included coming up with the concept for the Warriors’ “City” uniforms, which I wrote about a couple of years ago.

Mieuli, the son of Italian immigrants, grew up in the East Bay. Often described as “eccentric,” the bearded Mieuli was known for his trademark Hawaiian shirts, plaid pants, and Sherlock Holmes-style deerstalker caps. He traversed San Francisco on motorcycles, famously forgetting to bring them home on more than one occasion. Mieuli installed four ornate chandeliers in the rafters of the Cow Palace, his team’s cavernous, no frills home, acquired for $25,000 while on an offseason trip to Florence, Italy.

Meschery was a sentimental favorite of Mieuli, who, in a 1973 Boston Globe article, said “If I could have just been a basketball player, I would have liked to have been just like Tom Meschery. He played the game clean and hard.”

A subtle but meaningful element was included within the Warriors logo beginning in 1968, the season after Meschery’s 14 was mothballed. The team’s primary mark, which had previously consisted of the profile of a Native American headdress, was changed to echo the “City” decoration worn on the team’s uniforms. The number 14 was centered within the void above the Golden Gate Bridge, a tribute to the player whose number had been retired the previous year.

Unlike Mieuli’s affection for Meschery, however, his fondness for San Francisco began to wane by 1966, when he moved five of his team’s home games across the Bay to Oakland’s sparkling new arena, later known as the Oracle Arena. (The Warriors also hosted neutral site regular season games in places like San Jose, Fresno, Phoenix, and Eugene, Oregon during this era.) In 1970-71 the Warriors pivoted back and forth between the aging Cow Palace, the San Francisco Civic Auditorium, and Oakland. Average game attendance at the “Civic” was a paltry 2,766, while the Cow Palace hosted 5,320 customers per game and Oakland averaged a comparatively stellar 6,775. Even a cursory glance at the numbers revealed that the team’s future would clearly lie in the East Bay.

Finally, in 1971, Mieuli hatched a plan for his team to play 21 home games in Oakland and 20 home games in San Diego, which had recently been abandoned by the Rockets. The Warriors would therefore be transformed into a team that belonged to all of California, and he rechristened them the Golden State Warriors, making it official on August 2, 1971. Less than two weeks later the team scaled back their plans, announcing that the San Diego portion of the home schedule would be limited to but six contests. They also unveiled a revised logo at this time, in which Tom Meschery’s number 14 was arguably the most prominent element.

The inclusion of Meschery’s number was never formally trumpeted by the team, leaving sharp-eyed observers to wonder about its significance. There are numerous queries by newspaper readers about the mysterious digits from years following its introduction, but half a century and three NBA titles later, the logo tribute is seemly a forgotten thing.

The 14 quietly disappeared from the Warriors’ logo in 1974-75, the season that the team finally broke through for its first NBA championship in the Bay Area. By the following year Mieuli was contemplating another name change, this time to Oakland Warriors. He was reportedly talked out of it by the team’s ticket manager, who told him that ticket sales were equally divided on both sides of the bay. The Warriors moved into San Francisco’s new $500 million Chase Center in 2019. Meschery’s number 14 retired number banner resides in the arena’s rafters, wedged between Wilt Chamberlain’s 13 and Al Attles’s 16. While the Warriors have permanently put aside a total of six different uniform numbers, only one of them can claim the singular distinction of having been part of the team’s official logo.